Discrimination Is Human

Why we need discrimination, contrary to current ideological conditioning. This week’s issue is about chatbots, conformism, and the question of why.

Despite the current mainstream mission to eradicate all forms of discrimination and impose a complete societal reconditioning, discrimination is not merely an unfortunate social ill or a matter of singling out or belittling others. It is an intrinsic aspect of human behavior. This is not a flaw; it is a survival mechanism honed over millennia of evolution. The purpose of discrimination is to make distinctions, draw boundaries, and form judgments based on subjective values. It’s how humans and animals alike make sense of the world. Without the ability to discriminate, we would struggle to make even the simplest decisions necessary for our survival.

In evolutionary biology, discrimination plays a critical role in mate selection, ensuring that individuals choose the best possible partners to pass on their genes. Similarly, it helps animals, including humans, identify and avoid danger—whether by steering clear of predators or making judgments about risky social encounters. Discrimination in these contexts is both a natural and beneficial function. Moreover, this isn’t limited to biological survival; our psychological well-being also depends on authentic, freely chosen relationships. Genuine social bonds and authentic expressions—those not coerced by external forces—are crucial for mental health.

Do we really want laws that restrict this inherently human function just because it offends our sensibilities? When you mandate behavior, forcing people to act in ways that don’t align with their true emotional state, it breeds inauthenticity, invites artificiality, and corrodes the trust necessary for meaningful connections. Wouldn’t it be better if people were granted the freedom to be true, even if that means certain discriminating behavior and opinions become offensive because they don’t align with the mainstream? When discrimination is criminalized, and someone expresses kindness, how can we know it’s genuine?

Misconceptions About Discrimination

Discrimination, in everyday language, usually refers to derogatory discrimination, meaning the disadvantaging or demeaning of groups or individuals based on certain discriminatory (i.e., distinguishing) value judgments or due to unreflective, sometimes unconscious attitudes, prejudices, or emotional associations.

In a value-neutral sense, discrimination refers to the separation or differential treatment of objects. Outside the realm of certain social sciences, where the term often takes on more subjective connotations, this original meaning is used across the technical languages of all other serious scientific disciplines (excluding applied sciences that overlap with social sciences, such as public health or law).

Technically, without the use of adjectives or prepositions (e.g. “discriminate against”, “discriminate between”), discrimination is neutral, referring to the ability to make a distinction or judgment between different things.

Just as Switzerland has been losing its neutrality in banking secrecy due to pressure from external interest groups, the term “discrimination” has similarly evolved to acquire a negative connotation—a result of social and political forces, not scientific development. This semantic shift primarily began in the 20th century as discussions of vague concepts like “equality” and “social justice” emerged, and the term became associated with unfair treatment based on certain characteristics.

Interestingly, the creative scrutiny of the German language has given birth to a differentiation in terminology to address this linguistic distinction and clarify intent with “Diskriminierung” (increasingly used in a pejorative sense as the term loses its definitional precision) and “Diskrimination” (value-neutral). The latter is the very same word as the English “discrimination,” yet it is rarely used anymore as we ideologically move toward understanding discrimination as generally pejorative.

Even if we follow this semantic shift and accept a purely negative connotation, pejorative discrimination is still a deeply human behavior. As humans, we rarely make value-free distinctions between things. Human decision-making is influenced by biases, emotions, and personal values. The reasons people differentiate—discriminate—are mostly subjective. Even in cases of seemingly objective methods, such as hiring decisions, medical diagnoses, or court rulings, the forces of subjectivity persist beneath the veneer of objectivity and cannot be entirely eradicated. Thus, discrimination is typically either favorable or unfavorable.

It is an absurd presumption to expect people to make objective, non-judgmental distinctions in daily life, let alone eliminate pejorative discrimination entirely. This idea is ideological and unsupported by serious sciences such as biology, behavioral psychology, or sociology. No species could survive without discrimination.

Our entire value system is built on distinctions—discriminations—and the moralization of these distinctions: right and wrong, good and evil, acceptable and unacceptable. Thus, the more intriguing question is on what basis discrimination is deemed legitimate or illegitimate, and who holds the authority to define this.

Embracing Prejudice

Even prejudice—often considered one of the most negative forms of discrimination—evolved as a heuristic, a mental shortcut that enabled early humans to assess threats quickly in their environment. These snap judgments allowed our ancestors to protect themselves from potential dangers without expending excessive cognitive resources. Then as now, prejudice alerts us to legitimate threats based on past experiences.

The caveat is that in the complexity of modern society, particularly in our globalized and interconnected world, prejudices are less adaptive. When rigidly applied to social categories like race, gender, or ethnicity, they may conflict with rapidly shifting contemporary values and ideologies such as “equality.”

In some cases, prejudices perpetuate unnecessary conflict and social stagnation. However, these behaviors remain deeply ingrained in our biology and psychology—they are not inherently malevolent, but simply not optimally adapted to the world we have been creating.

The Freedom to Discriminate

Discrimination is also an expression of freedom. Humans and animals alike exercise varying degrees of instinctive discrimination to survive and maintain independence and autonomy. Every action and choice we make involves distinguishing between options, making discrimination a cornerstone of individual liberty, from choosing friends to selecting a career path. When we remove the freedom to discriminate—whether in social, personal, or professional contexts—we risk undermining human agency. To act freely is to discriminate based on personal judgment, values, and desires.

If discrimination is an inherent part of human psychology, including infamous forms such as racism (discrimination based on race or ethnicity), sexism (discrimination based on sex or gender), ableism (discrimination based on (dis)ability), and classism (discrimination based on social class), how can we justify restricting it? The result is a society where politeness and tolerance become performative rather than authentic, fostering distrust and confusion. Additionally, it creates a false sense of security for the protected group. The mental process of discrimination remains active—only its expression is criminalized.

To protect both society and its individuals, isn’t it sufficient—and more effective—to criminalize potential harmful results of discrimination such as murder, theft, vandalism, or arson instead of discrimination itself; the way most legal systems already operate?

The attempt to regulate or eliminate discrimination is akin to regulating thought or desire—an ideological fantasy.

From Individual to Crowd Discrimination

Wherever individuals gather, their discriminating tendencies culminate in collective societal, systemic, or structural discrimination, depending on the level of institutionalization. It simply means discriminatory treatment is now conducted by a group of individuals—society or its institutions—embedded, expressed, and enforced through their habits, rites, procedures, policies, and laws.

Most of what is labeled structural discrimination is simply the outcome of organic growth and practical organization. Institutions such as monasteries, military units, fire departments, construction and engineering units, or religious organizations legitimately discriminate by gender, ethnicity, age, or physical ability to preserve their effectiveness, cohesion, and societal roles. These institutions operate on the principle that not all individuals are suited for every role, and certain distinctions—whether based on physical ability, gender, or cultural background—are necessary to maintain their essential functions.

The military’s gender-based requirements are not arbitrary but are designed to ensure that combat units are physically capable of meeting the demands of warfare. Indigenous tribal governments prioritize membership based on ethnicity to preserve cultural heritage and sovereignty. Christianity, Islam, and Judaism select men as their priests, imams, and rabbis to conserve the integrity of their teachings. Universities and scholarship foundations discriminate by intelligence, performance, wealth, or socioeconomic background to maintain their level of excellence. These forms of discrimination are not oppressive; they are essential to the survival and proper functioning of these institutions, and thus, society as a whole.

It is only natural that these structures, evaluations, and processes are continuously challenged over time as beliefs and ideologies evolve (e.g., feminism) or as the social composition of a population changes (e.g., immigration). However, changes brought about by this continuous molding process don’t happen overnight, especially in societies composed of millions of individuals.

The survival of any society largely depends on the practicality, productivity, integrity, and resilience of its organizational structure. Thus, adaptation takes time, and societal structures naturally resist change to preserve the above functions and to prevent the collapse of institutions.

Therefore, any structural value-neutral discrimination inevitably results in individually perceived subjective advantages and disadvantages. This is not inherently unfair or pejorative; it simply means that not everyone’s individual needs can be met simultaneously. For society to exist, it must define a sustainable moral standard that applies universally.

The larger a social group grows within a society—especially one that perceives itself as disadvantaged by the system’s discriminatory structure—the stronger its ability to influence and reshape societal norms to its own advantage. Time will show whether these changes are sustainable or not.

In any case, for such structural changes to happen, the majority of individuals must change their beliefs out of free will—or at least perceive that this change comes from their free will.

Pricing and distribution of food or housing, waiting times for medical services, or access to public services often depend on ethnic or gender discrimination. A female student might search for a girl or homosexual man to share an apartment, discriminating by sexuality. A restaurant might not serve people with certain dietary preferences, discriminating by health or religion. A clothing store might offer discounts to elders or students, discriminating by age. A club or bar might offer free entry or drinks to women, discriminating by gender.

By the way, the most apparent and rigorous discrimination happens in the dating, mating, and marriage markets, where it all comes together: race, health, ethnicity, wealth, age, social status, religion, politics, intelligence—the list goes on.

None of these things are inherently unfair or pejorative. They are simply the result of what the majority of individuals within a society have agreed upon as an equitable compromise for their needs and desires.

Developing Agency and Resilience

Labeling discrimination as unnatural, inhumane, or unfair is, in itself, a form of discrimination. Those fighting it display the very discriminatory behavior they seek to condemn. Of course, it’s not truly the human behavior trait of discrimination itself they fight against but rather feelings, perceptions, and opinions that don’t serve and align with their own. Such fight is nothing but a self-serving moral veneer to label one’s own discriminatory behavior as just and others’ as vile.

Many ideologies intentionally create contradictions and confusion, fostering shame, fear, and resentment. In this emotional turmoil, exploitation and control are easily established.

Discrimination is not a societal ill but an essential aspect of free thought and free will. Every action we take depends on it. Feeling shame or guilt for this natural behavior is a result of conditioning and manipulation, not personal inadequacy.

Don’t accept the shame or guilt others try to induce in you for whatever arises within naturally—unless what has arisen violates your own values. Don’t let ideologies manipulate you into compliance. Develop and learn to trust your own moral compass.

Have a phenomenal week!

⏤Ferdinand

✨ Sunday’s Sparks

🌐 Website: GetHuman

service that allows you to search for company names and provides you with customer service phone numbers that connect you to a real human. This is particularly helpful in times when customer service is replaced by surprisingly unintelligent artificial intelligence and chatbots seemingly designed to drive customers to insanity.

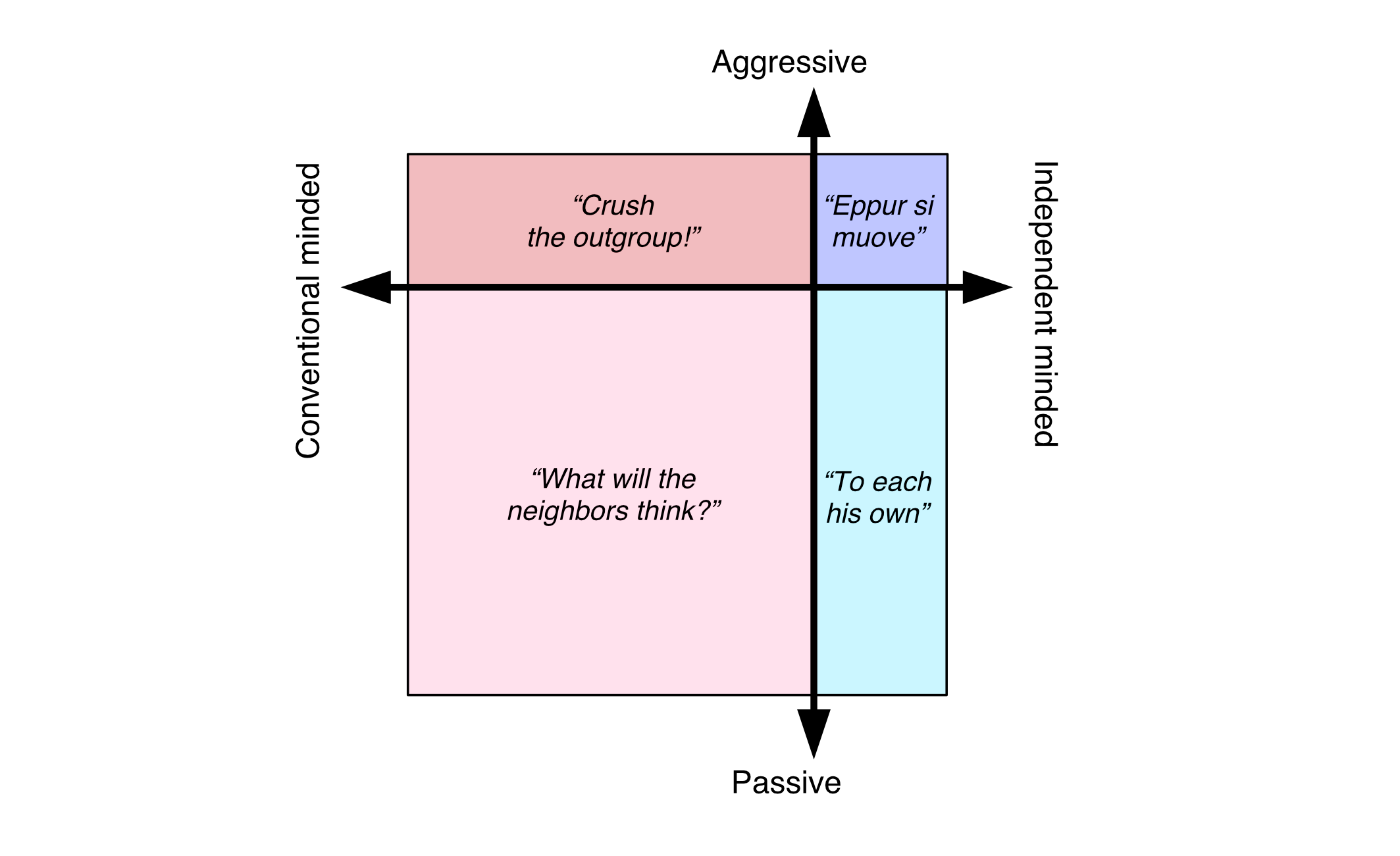

📝 Article: The Four Quadrants of Conformism

Terrific elaboration on the classification of four different societal groups according to the two dimensions degree of conformism and degree of aggressiveness.

A Cartesian coordinate system with an x-axis from conventional-minded on the left to independent-minded on the right, and a y-axis from passive at the bottom to aggressive at the top, results in four quadrants:

- Upper left: The aggressively conventional-minded, the tattletales.

They believe that rules must be obeyed, and disobedience must be punished.

Distinctive call: “Crush the outgroup!” - Lower left: The passively conventional-minded, the sheep.

They’re careful to obey the rules and worry that others’ disobedience will be punished, but they don’t ensure or foster punishment.

Distinctive call: “What will the neighbors think?” - Lower right: The passively independent-minded, the dreamy ones.

They simply don’t care much about rules.

Distinctive call: “To each his own.” - Upper right: The aggressively independent-minded, the naughty ones.

Their first impulse is to question any rule, and disobedience is their default reaction to the attempt to be subordinated to a rule.

Distinctive call: “Eppur si muove.”

It’s important to note that there are more passive people than aggressive ones, and more conventional-minded people than independent-minded ones. Also, the system is societally universal, since people from different cultures would occupy the same quadrant; one’s quadrant depends mainly on personality, not the nature of the rules.

Princeton professor Robert George recently wrote:

‘I sometimes ask students what their position on slavery would have been had they been white and living in the South before abolition. Guess what? They all would have been abolitionists! They all would have bravely spoken out against slavery, and worked tirelessly against it.’

He's too polite to say so, but of course they wouldn't. And indeed, our default assumption should not merely be that his students would, on average, have behaved the same way people did at the time, but that the ones who are aggressively conventional-minded today would have been aggressively conventional-minded then too. In other words, that they'd not only not have fought against slavery, but that they'd have been among its staunchest defenders.

Why do the independent-minded need to be protected, though? Because they have all the new ideas. To be a successful scientist, for example, it's not enough just to be right. You have to be right when everyone else is wrong. Conventional-minded people can't do that. For similar reasons, all successful startup CEOs are not merely independent-minded, but aggressively so. So it's no coincidence that societies prosper only to the extent that they have customs for keeping the conventional-minded at bay.

In the last few years, many of us have noticed that the customs protecting free inquiry have been weakened. Some say we're overreacting — that they haven't been weakened very much, or that they've been weakened in the service of a greater good. The latter I'll dispose of immediately. When the conventional-minded get the upper hand, they always say it's in the service of a greater good. It just happens to be a different, incompatible greater good each time.

As for the former worry, that the independent-minded are being oversensitive, and that free inquiry hasn't been shut down that much, you can't judge that unless you are yourself independent-minded. You can't know how much of the space of ideas is being lopped off unless you have them, and only the independent-minded have the ones at the edges. Precisely because of this, they tend to be very sensitive to changes in how freely one can explore ideas. They're the canaries in this coalmine.

Any process for deciding which ideas to ban is bound to make mistakes. All the more so because no one intelligent wants to undertake that kind of work, so it ends up being done by the stupid. And when a process makes a lot of mistakes, you need to leave a margin for error. Which in this case means you need to ban fewer ideas than you'd like to. But that's hard for the aggressively conventional-minded to do, partly because they enjoy seeing people punished, as they have since they were children, and partly because they compete with one another. Enforcers of orthodoxy can't allow a borderline idea to exist, because that gives other enforcers an opportunity to one-up them in the moral purity department, and perhaps even to turn enforcer upon them. So instead of getting the margin for error we need, we get the opposite: a race to the bottom in which any idea that seems at all bannable ends up being banned.

🎬 YouTube Video: Richard Feynman. Why.

Richard Feynman was undoubtedly one of the greatest teachers of modern history. He was a theoretical physicist recognized for his work in the fields of particle physics, quantum mechanics, and electrodynamics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1965. He also assisted in the development of the atomic bomb.

In this excerpt, he explains the limitations of answering the question of why. Feynman brilliantly deduces how comprehension of any subject is dependent on one’s ability to relate it to other, already known parameters within a familiar and (assumed) true framework. When asking the question of why, one needs to know what they’re permitted to understand.

I really can’t do a good job—any job—of explaining magnetic force in terms of something else you’re more familiar with, because I don’t understand it in terms of anything else that you’re more familiar with.

💡 Sunday’s Wisdom

When we repeat the same words and phrases that appear in the daily media, we accept the absence of a larger framework. To have such a framework requires more concepts, and having more concepts requires reading. So get the screens out of your room and surround yourself with books.

From On Tyranny by TIMOTHY SNYDER.

Captured and resurfaced using the phenomenal Kindle reader.

Did you enjoy this issue? If you draw value from Sunday Sparks please consider contributing to this publication’s financial freedom.

Flows straight into content, not coffee.